Conflict is a common occurrence in the classroom, but fairy stories can be used to help children come up with their own resolutions...

How many times does a conflict arise because a person makes an assumption about the best way to get what he needs? Worse still, he makes assumptions about the person with whom he’s at odds. At some level he believes his actions are justified, even though he may not have consciously thought them through, or considered the consequences.

That being the case, it’s not surprising how many times in a day our students find themselves involved in conflicts which, in their hearts, they know are unnecessarily difficult. When they are focused on getting what they want and it is causing a problem, it is worth checking what need they are trying to satisfy by insisting on a particular course of action. It is important to do this because often they are not the same thing at all.

Imagine a situation where two students are arguing but they agree, or are asked, to compromise. What happens when one, or both of them, is unable to recognise the difference between what they say they want and what they really need? In this scenario, there is every possibility they will agree to a compromise that causes an additional personal conflict because they unintentionally conceded to limit or give up on something that is very important to them – a basic need. This can be a physical or emotional need such as respect, freedom, dignity; or simply keeping a promise. How easy do you think it is to stick to a compromise that negatively impacts on a basic need? Typically, the agreed compromise is not sustainable or, if it is, one or both sides start to build up resentment, which inevitably comes out later and we find ourselves in a vicious cycle.

My new book, Storytelling for Better Behaviour (Speechmark, 2012), provides an alternative way for primary pupils to resolve conflicts – both in and out of the classroom – by considering the actions of characters in fairy tales. It demonstrates a methodical process that pupils can use to consider the underlying needs or emotions that motivate people’s choices and how such needs may have influenced well-known fictional characters from fairy stories. Building on this, students consider alternative ways for these characters to meet their needs and achieve their goals without causing harm to themselves or others.

Fairy stories and children’s tales have a long and respected tradition associated with moral guidance and social wisdom. Combining these timeless traditions with a set of graphic organisers (GOs), it is possible to use the conflicts experienced by fictional characters to teach pupils a Socratic method of scaffolding questions that respects and considers the feelings of others while unveiling the emotions and unmet needs that led to a conflict or an undesirable outcome. This vicarious process can give language to students’ own illusive thoughts that previously may have driven inappropriate behaviour.

Stories also provide safe places in which we can explore common emotional themes and problems. Listeners may recognise and identify with issues without needing to disclose personal information. As such, stories have a therapeutic use and offer the potential for internal reflection.

Through fairy stories, even the very youngest of audiences have the opportunity to analyse, reflect, ponder and consider motivations, and the consequences of characters’ choices. This means stories are well placed to develop an empathic response in the listener, creating the potential for them to apply that empathy within his or her own life.

Students will enjoy helping the Big Bad Wolf, Skuba and Fagin turn over a new leaf. First by identifying a win-win solution, one that satisfies all the story’s characters, and then by setting and planning targets that will see them achieve their goals. Finally, students will be able to create a new ending, or beginning, for the stories used so that all the characters do indeed live happily ever after.

Jasmine was five years old when she and her classmates used this method to consider the conflict between the Big Bad Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood.

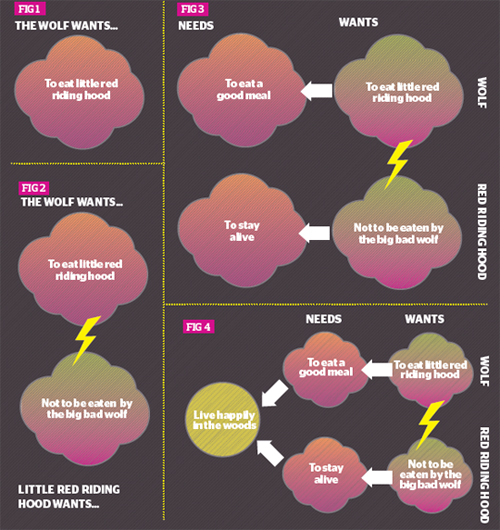

They began by analysing the conflict. On the one hand the Wolf wanted to eat Little Red Riding Hood.FIG 1

Not surprisingly, Little Red Riding Hood did not want to be eaten. FIG 2

Having established what each side wanted, they considered what need each want would satisfy. FIG 3

Next, children considered if the Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood had anything in common. This seemed unlikely, but if Jasmine and her classmates could suggest something upon which the two characters could agree, they would have something to build on. To do this, the class imagined what it would be like if both sides had what they needed - if the Wolf could eat a good meal and Little Red Riding Hood could stay alive. The class decided this would allow them to live happily in the woods. FIG 4

Analysing the conflict in this way allowed the students to clarify what each side wanted and why they wanted it. They also uncovered a shared goal, one both the Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood could work towards. The class were then shown how to find a solution to this problem by simply reading the organiser, starting with the shared goal:

To live happily in the woods the wolf needs to eat a good meal. To eat a good meal the wolf must eat Little Red Riding Hood. You’ll notice that the syntax changed, so instead of using ‘need’ we now articulate the want as something the wolf says he ‘must’ do or have.

The class considered if they could find a win-win solution by focusing on each sides’ wants. They agreed this would be impossible because the two wants are in conflict. After all, Little Red Riding Hood can’t be eaten and not eaten.

However, Little Red Riding Hood’s need to stay alive and the Wolf’s need to eat are not in conflict. So if the class could find an alternative meal for the Wolf, they might also find a solution to this problem. To help the Wolf work this out for himself, they imagined why he thought he could only get a good meal if he ate Little Red Riding Hood? What assumptions had he made?

To work this out, the children added ‘because’ to the end of the last sentence. We often say ‘because’ when we are explaining why something happened. But it also gives an excuse for what is happening, excuses that help us feel OK about our actions.

The class imagined all the things the Wolf might say that would make his behaviour seem acceptable. How he justifies his behaviour to himself, and what excuses he has for the things he does. His excuses are based on his assumptions. Most typically, the statement that follows ‘because’ is an assumption.

‘To live happily in the woods the wolf needs to eat a good meal. To eat a good meal the wolf must eat Little Red Riding Hood because…she is the only food available. Because…she would make a satisfying meal. Because…?

So is Little Red Riding Hood the only food available? When the class considered whether this was true, they were able to quickly remove this particular assumption as a viable reason.

Jasmine and her friends eventually decided that no living thing wants to be eaten and so re-wrote the story. The Wolf became a vegetarian and set up a Bistro in the woods with the help of Little Red Riding Hood and her mum. He bought some land from the woodchopper and grows all his own vegetables. When he has a surplus, he sells his produce to the local school for their healthy eating programme.

Jasmine could see that the Wolf had got into trouble because he had insisted on getting what he wanted. Jasmine now understood that what we say we want is not always what we need.

When Jasmine and her friends applied this process to themselves and a personal choice they had made, it allowed them to reflect and, in some cases, reconsider their decisions.

Jasmine considered the consequence of having something she loved. She loved dried mango, and because her mummy loved her, she always packed dried mango in her lunch box. Because Jasmine loved mango so much, she couldn’t resist eating it before anything else. But dried mango takes a long time to finish and Jasmine can never eat it all before the bell goes, and so she misses out on the rest of her lunch. A consequence of this is that she is very hungry. Dinner isn’t until much later and mummy does not like Jasmine to eat between meals. Jasmine recognised that being hungry when she came out of school meant she was also quite irritable. Being irritable meant that most afternoons Jasmine and her mum did not enjoy each other’s company!

Jasmine learnt how to explore consequences but, more importantly, she learnt how to look at them so she could work out where in the chain the problem started.

Jasmine came up with a solution (on her own) for a problem she had not recognised she had until she learnt this process. She could now see the effects of having what she wanted on the rest of her day. She decided to tell her mum she no longer wanted mango in her lunch box. The decision to change was very simple for her.

Do you think she would have been as happy to give up her mango if her mum or a midday supervisor had suggested it? Changing our behaviour is so much easier when we work out the consequences for ourselves.

Boosting children’s self esteem

Ace-Classroom-Support