Gill Matthews explores how visual images can be used in the classroom to stimulate creative writing...

I was thinking about a catchy title for this article and the saying ‘A picture paints a thousand words’ popped into my head. Ever keen to prevaricate, I typed the phrase into a search engine and came up with over 83000 results. Turning to the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, I discovered that I had the wording wrong. The expression is actually ‘One picture is worth ten thousand words’ - it was used in the 1920s as an advertising slogan for baking powder and, rightly or wrongly, cited as an ancient Chinese proverb. I was now at risk of getting carried away in my research and I thought, 1000 or 10000 words - does it really matter? The fact remains: pictures can, in a single glimpse, tell us an awful lot more than words convey in that same space or time.

There are two immediate and very obvious benefits of using visuals, in the form of paintings, photos and picture books, as stimuli for writing: first, they give children something to talk about; secondly, they give children something to write about. The place and importance of talk in the writing process is well recognised and is being supported by the National Strategies’ Talk for Writing materials. Talking gives children not only the opportunity orally to rehearse what they are going to write, but also the chance to explore ideas and develop the content of their writing. Many children seem to struggle with subject matter because their day-today encounters are, in their view, often limited. An image can provide them with vicarious experiences, and these, through exploration, can prompt and build ideas for writing.

Paintings and other artwork are a readily accessibly resource that can be used as a visual stimulus for writing. Since 1995, the National Gallery has run an annual initiative for primary schools called ‘Take One Picture’. Each year, the Gallery focuses on one particular painting and schools are encouraged to use it imaginatively as the stimulus for cross-curricular activities. A selection of the resulting work is displayed in the annual ‘Take One Picture’ exhibition at the National Gallery and on the website http://www.takeonepicture.org. Also available on the website are downloadable Teachers’ Notes, which are a good starting point for developing work around the current focus painting: The Umbrellas, by Renoir. The ideas given in the Teachers’ Notes can easily be adapted for use with other paintings. For example: asking children to think about what they could see, smell, touch, taste or feel if they were inside the painting; exploring their thoughts about the people they can see; what might be beyond the frame. Following this kind of discussion, children could write character or setting descriptions, a story based on the painting, a newspaper article, or poems that draw on elements of the artwork. Antony Browne’s book The Shape Game explores different responses to art and would tie in well with using paintings as a stimulus for writing.

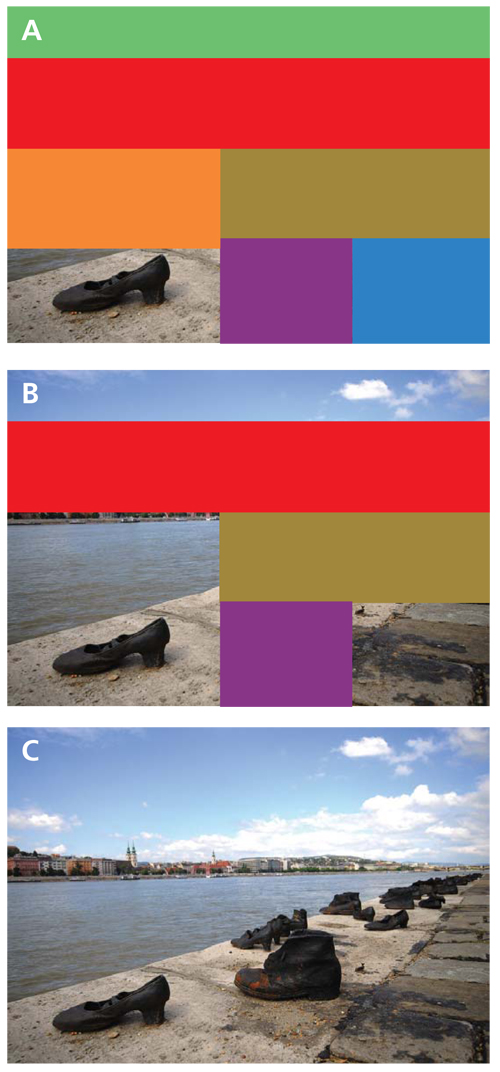

Once you start thinking about using visual images in the classroom, you do spot opportunities all around you. On a recent trip to Budapest, I noticed an unusual art installation and snapped it. It is a moving memorial to a group of Hungarian Jews who were shot on the banks of the Danube in 1944. I’ve used this in classrooms with children and on my CPD sessions on visual literacy, in order to encourage and develop close observation skills. I have set up the photo as a series of Powerpoint slides and masked the photo with seven coloured text boxes. I reveal the photograph bit by bit - leaving the full collection of shoes to be the last section shown. To support close observation, I ask questions en route such as, Where do you think this is? How can you tell? What do you think has happened? What do you expect to find behind the final strip? To whom do you think the shoes belong? This has led to poetry writing, writing in role as a news reporter, and obviously provides close links to work around the Second World War. But you don’t have to go to Budapest for photo opportunities. There seems to be a proliferation of contemporary lifesized statues in towns and cities around the world, as well as those depicting famous characters in realistic settings, such as the poet Patrick Kavanagh relaxing by a Dublin canal. Snaps of these could form the basis for discussion, or developing the key characters in a story (could someone have been frozen in time? How might that have happened?). It isn’t difficult to find examples of such sculptures on the internet, but keep your camera handy too. You never know what’s around the corner!

Once you start thinking about using visual images in the classroom, you do spot opportunities all around you. On a recent trip to Budapest, I noticed an unusual art installation and snapped it. It is a moving memorial to a group of Hungarian Jews who were shot on the banks of the Danube in 1944. I’ve used this in classrooms with children and on my CPD sessions on visual literacy, in order to encourage and develop close observation skills. I have set up the photo as a series of Powerpoint slides and masked the photo with seven coloured text boxes. I reveal the photograph bit by bit - leaving the full collection of shoes to be the last section shown. To support close observation, I ask questions en route such as, Where do you think this is? How can you tell? What do you think has happened? What do you expect to find behind the final strip? To whom do you think the shoes belong? This has led to poetry writing, writing in role as a news reporter, and obviously provides close links to work around the Second World War. But you don’t have to go to Budapest for photo opportunities. There seems to be a proliferation of contemporary lifesized statues in towns and cities around the world, as well as those depicting famous characters in realistic settings, such as the poet Patrick Kavanagh relaxing by a Dublin canal. Snaps of these could form the basis for discussion, or developing the key characters in a story (could someone have been frozen in time? How might that have happened?). It isn’t difficult to find examples of such sculptures on the internet, but keep your camera handy too. You never know what’s around the corner!

Finally, let’s move onto picture books. One issue is where to start, as huge numbers of titles are published every year. Some lend themselves to use as visual stimuli, others don’t. Those that do, have detailed illustrations that add meaning and often another dimension to the story. The Kate Greenaway Medal is an annual award for an outstanding illustrated book for children. Every year a number of books are shortlisted, and the details are published on the website. Take a look at the websit http://www.carnegiegreenaway.org.uk Here you will find resources for each book on the shortlist to support the development of visual literacy skills. These take the form of a series of questions that focus on one double page spread from each title. They can be explored in whole class, group or paired situations. The aims of the activities, according to the website, are to:

• increase the interaction with, and enjoyment of, picture books for children of all ages

• develop children’s confidence and vocabulary to respond to what they see – to observe and describe

• encourage them to build on their previous experience, imagination and understanding to make sense of visual information – to interpret

• consider a variety of graphic forms and their interaction with a text in order to convey layers of meaning – to appreciate

• recognise different styles and techniques used by a variety of illustrators – to analyse

• begin to recognise and appreciate visual metaphor, irony, puns and jokes etc. – to participate

I’ve found these really useful in terms of identifying and categorising the types of questions that can be asked about visual images – exploring the use of colour, light and shade, layout, and characters’ feelings and emotions, as well as relationships between images and text.

Written responses to this detailed reading and interpretation of an image can vary widely, from simple character or setting descriptions that describe what can be seen on the page to more sophisticated descriptions that create mood, atmosphere or tension by drawing on some of the illustrator’s techniques. Of course, writing isn’t the only way of responding to an image. Children could explore their responses through art (including the creation of photographs, art installations and sculptures), drama or music.

Written responses to this detailed reading and interpretation of an image can vary widely, from simple character or setting descriptions that describe what can be seen on the page to more sophisticated descriptions that create mood, atmosphere or tension by drawing on some of the illustrator’s techniques. Of course, writing isn’t the only way of responding to an image. Children could explore their responses through art (including the creation of photographs, art installations and sculptures), drama or music.

To end on a practical note, and I know this sounds obvious, if you are planning to use still images with children, remember that they need to be able to see them in detail. Images can be scanned into a computer and displayed on a whiteboard, but they tend to be less clear than the original. One piece of equipment that is invaluable when using still images is a visualiser. This looks rather like an overhead projector but is a small camera that projects very clear images of whatever it is filming onto a whiteboard. So, it can be used to show an illustration from a picture book or pupils’ work, even to demonstrate how to create an eight page book from a single piece of paper. Hopefully, the children will then demonstrate that a picture can stimulate 1000 – or even 10000 – words.

Child’s eye media provide some top tips on how films, television and animations can provide fantastic stimuli for writing…

21st century children are very media literate, and the right programmes can:

• Provide a great starting point for discussion

• Develop children’s knowledge and understanding of the world – it is not always possible to take a group of children to a fire station or a mosque – but using appropriate films is the next best thing

• Inspire children’s role-play

• Help children learn new vocabulary and understand new concepts

• Stimulate creativity

With this in mind, the following points should be considered when selecting programmes:

• Choose programmes and DVDs without too many special effects. Young children learn only gradually how to differentiate between what is real, and what is not real on television.

• Look for programmes with a single narrative voice.

• Remember that children’s brains are hard-wired for narrative - so look out for documentaries with a strong story arc, rather than ‘clips’, which are harder for young children to interpret.

• Use films that feature real children and live action where possible – children’s television channels are dominated by animations, and youngsters are hungry to learn about the world around them.

Child’s Eye Media specialises in making films and other educational resources for children aged 3–8. The company’s multi award-winning films are all shot from a child’s eye view, and feature young children exploring the world around them. Child’s Eye Media is now making a Site Licence available for its films. This will allow teachers and pupils to access and copy the resources on all devices within the school – as a stimulus for personalised learning as well as whole class viewing. For more information, go to http://www.childseyemedia.com

In her next article, Gill will explore the use of multimodal texts in the classroom. For examples of units of work on visual literacy, created by teachers, have a look at the Noticeboard pages on Gill’s website http://www.gillmatthews.co.uk

The side effects of teaching music

Ace-Music

Easy ways to combat teacher stress

Ace-Heads

If your marking doesn’t affect pupil progress - stop it!

Ace-Classroom-Support